Whiter Whites

September 5, 2014 Some people prefer to see the world as black and white, but the reality is that nothing is that certain. Scientifically, pure black and pure white are technologically useful, but they are difficult to obtain. I wrote about various aspects of white and black in some previous articles (Thin and Black, August 2, 2013, Paint it Black, February 13, 2013, Very White and Very Black, November 23, 2011, and White Roofs, March 19, 2012). One measure of the whiteness of an object is its diffuse reflectivity, known also as albedo (from the Latin, alba, "white"). Albedo is the ratio of reflected to incident light, but it's defined at each wavelength of light. What this means is that something that's black at visible wavelengths might be white at other wavelengths. The purest white has an albedo of one, and the purest black has an albedo of zero. | Uncooked, polished, white jasmine rice from Thailand. The characteristic aroma of white jasmine rice comes from 2-Acetyl-1-pyrroline (C6H9NO). (Photograph by Takeaway, via Wikimedia Commons.) |

|

|

| Cyphochilus beetle. (left image and right image by Lorenzo Cortese and Silvia Vignolini, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.) |

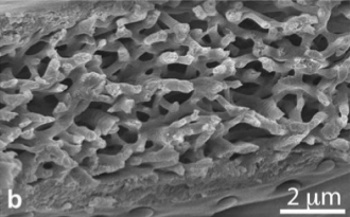

| Scanning electron micrograph of the cross-section of the scales of the Cyphochilus beetle. (Fig. 1b of ref. 8, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.[8]) |

"Current technology is not able to produce a coating as white as these beetles can in such a thin layer... In order to survive, these beetles need to optimize their optical response but this comes with the strong constraint of using as little material as possible in order to save energy and to keep the scales light enough in order to fly. Curiously, these beetles succeed in this task using chitin, which has a relatively low refractive index."[9]A random collection of scattering centers by themselves wouldn't give rise to such an intense white as with the chitin material. It's the particular arrangement of the filaments that allows this, and this high-brightness white comes from a material with a low mass per unit area.[8-9] The artificial production of such structures would have many applications, such as making whiter paper, plastics and paints.[8] Says Vignolini,

"The lessons we are learning from these beetles is two-fold... On one hand, we now know how to look to improve scattering strength of a given structure by varying its geometry. On the other hand the use of strongly scattering materials, such as the particles commonly used for white paint, is not mandatory to achieve an ultra-white coating."[8]The research was funded by the European Research Council and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.[8]

References:

- John Lehman, Evangelos Theocharous, George Eppeldauer and Chris Pannell, "Gold-black coatings for freestanding pyroelectric detectors," Measurement Science and Technology, vol. 14, no. 7 (July, 2003).

- W. Becker, R. Fettig and W. Ruppel, "Optical and electrical properties of black gold layers in the far infrared," Infrared Physics & Technology, vol. 40, no. 6 (December, 1999), pp. 431-445.

- Chih-Ming Wang, Ying-Chung Chen, Maw-Shung Lee and Kun-Jer Chen, "Microstructure and Absorption Property of Silver-Black Coatings," Jap. J. Appl. Phys. vol. 39, Part 1, no. 2A, (February 15, 2000) pp. 551-554.

- Zu-Po Yang, Lijie Ci, James A. Bur, Shawn-Yu Lin and Pulickel M. Ajayan, "Experimental Observation of an Extremely Dark Material Made By a Low-Density Nanotube Array," Nano Lett., vol. 8, no. 2 (February, 2008), pp 446-451.

- Researchers Develop Darkest Man-Made Material, Inside Rensselaer, vol. 2, no. 2, January 31, 2008.

- Kohei Mizuno, Juntaro Ishii, Hideo Kishida, Yuhei Hayamizu, Satoshi Yasuda, Don N. Futaba, Motoo Yumura and Kenji Hata, "A black body absorber from vertically aligned single-walled carbon nanotubes," Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 106, no. 15 (April 14, 2009), pp. 6044-6047.

- Lori Keesey and Ed Campion, "NASA Develops Super-Black Material That Absorbs Light Across Multiple Wavelength Bands," NASA Goddard Press Release No. 11-070, November 8, 2011.

- Matteo Burresi, Lorenzo Cortese, Lorenzo Pattelli, Mathias Kolle, Peter Vukusic, Diederik S. Wiersma, Ullrich Steiner, and Silvia Vignolini, "Bright-White Beetle Scales Optimise Multiple Scattering of Light," Scientific Reports, vol. 4, article no. 6075 (August 15, 2014), doi:10.1038/srep06075. This is an open access article with a pdf file, here.

- The beetle's white album, University of Cambridge Press Release, August 15, 2014.

- W. Becker, R. Fettig and W. Ruppel, "Optical and electrical properties of black gold layers in the far infrared," Infrared Physics & Technology, vol. 40, no. 6 (December, 1999), pp. 431-445.