War Elephant DNA

February 7, 2014 The traditional elementary school paradigm is "reading, writing, and 'rithmetic," but the study of history has somehow entered the mix, along with science. There's a reason to study history. As explained by philosopher, George Santayana (1863-1952), in The Life of Reason, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it." The study of history can also be entertaining. In a world presently overrun with Jaydens and Aidens,[1] where else can you encounter such interesting names as Hasdrubal the Fair. Hasdrubal the Fair was the brother-in-law of Hannibal, the formidable opponent to the Roman Republic in the Second Punic War. Most wars have their slogans, and the Roman slogan for this war was "Carthago delenda est;" that is, "Carthage must be destroyed." Hannibal is most famous for marching his army through the Pyrenees and the Alps from Iberia into Northern Italy in 218 BC. Army marches, even through snow-covered mountains, are not that interesting, but Hannibal's march is noted for its contingent of war elephants. Hannibal was able to occupy a portion of Italy for fifteen years, but he was defeated by Scipio Africanus at the Battle of Zama. | Carthaginian war elephants attack the Roman infantry at the Battle of Zama, 202 BC. (Illustration, circa 1890, by Henri-Paul Motte (1846-1922), via Wikimedia Commons.) |

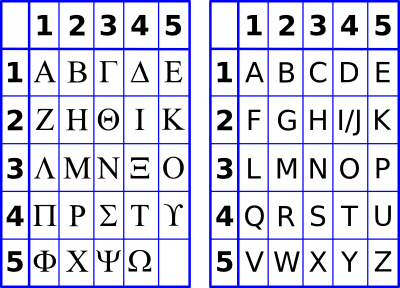

| Tables for the Polybius square cipher. Greek has 24 characters compared with 26 for English. For English, I and J are combined. (Illustration by the author using Inkscape.) |

"The way in which these animals fight is as follows. With their tusks firmly interlocked they shove with all their might, each trying to force the other to give ground, until the one who proves strongest pushes aside the other's trunk, and then, when he has once made him turn and has him in the flank, he gores him with his tusks as a bull does with his horns. Most of Ptolemy's elephants, however, declined the combat, as is the habit of African elephants; for unable to stand the smell and the trumpeting of the Indian elephants, and terrified, I suppose, also by their great size and strength, they at once turn tail and take to flight before they get near them. This is what happened on the present occasion; and when Ptolemy's elephants were thus thrown into confusion and driven back on their own lines, Ptolemy's guard gave way under the pressure of the animals."Despite this, Ptolemy won the battle and gained control of the region around Syria. Less than two decades later, Egypt lost this same region to the Seleucid Empire. There's been considerable speculation why Ptolemy's elephants ran from the fight. The traditional explanation was that his African elephants were smaller than Ptolemy's Asian elephants. These African elephants might have been forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis), not the larger savanna elephants (Loxodonta africana);[4] or, a now extinct smaller elephant species. This issue was solved as part of a genomic study of an endangered population of Eritrean elephants by scientists from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign (Urbana, Illinois), the Ministry of Agriculture (Asmara, Eritrea), the National Cancer Institute, (Frederick, Maryland), the University of Washington (Tacoma, Washington), and the Elephant Research Foundation (Bloomfield Hills, Michigan). The research team was led by Alfred Roca, a professor of Animal Sciences at the University of Illinois.[5-6] The elephants are descendants from the original population used as war elephants by Ptolemy. The research study found that Eritrean elephants have nuclear and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) markers of savanna elephants.[5] There were no discovered links to forest or Asian elephants.[6] Since mitochondrial DNA is passed from mother to offspring, it would indicate whether any forest or Asian elephants had been in the Eritrean population at any time.[6] Says Roca,

"In some sense, mtDNA is the ideal marker because it not only tells you what's there now, but it's an indication of what had been there in the past because it doesn't really get replaced even when the species changes... The most convincing evidence is the lack of mtDNA from forest elephants in Eritrea."[6]This research was supported by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.[6]

| A modern war elephant. An M1A2 tank, complete with trunk. (Modified image from Wikimedia Commons.) |

References:

- Top 10 Baby Names for 2012, US Social Security Administration Web Site.

- Matthew Backhouse, "Toxic wine led to Greek tragedy: NZ scientist," New Zealand Herald, January 11, 2014 .

- Polybius, "The Histories of Polybius," Book V, published in vol. 3 of the Loeb Classical Library (1922-1927). The text is in the public domain.

- William Gowers, "African Elephants and Ancient Authors," African Affairs, vol. 47, no. 188 (July, 1948), pp. 173-180.

- Adam L. Brandt, Yohannes Hagos, Yohannes Yacob, Victor A. David, Nicholas J. Georgiadis, Jeheskel Shoshani and Alfred L. Roca, "The Elephants of Gash-Barka, Eritrea: Nuclear and Mitochondrial Genetic Patterns," To Appear, J Heredity (2013) doi: 10.1093/jhered/est078. PDF file available, here.

- Claire Sturgeon, "War Elephant Myths Debunked by DNA," University of Illinois Press Release, January 9, 2014.

- Matthew Backhouse, "Toxic wine led to Greek tragedy: NZ scientist," New Zealand Herald, January 11, 2014 .