Violin Evolution

October 31, 2014 Nature, through evolutionary processes, has been changing and "forking" the body plans of organisms since the emergence, about 3.5 billion years ago, of life on Earth. Everywhere there's an ecological niche, nature tries to fill it, sometimes with unusual organisms, such as those discovered in the depths of the sea (see drawing). | The Humpback anglerfish (Melanocetus johnsonii), a species of the aptly named black seadevil (Melanocetidae). This fish is found at sea depths of up to 6,600 feet (2 kilometers). (Via Wikimedia Commons.) |

| George Frideric Handel as he appears on a 1985 German postage stamp. 1985 was the 300th anniversary of Handel's birth, and the birth of Johann Sebastian Bach. I recommend the recordings of the Academy of Ancient Music for those interested in early music. (Via Wikimedia Commons.)[3-4] |

|

| A Stadivarius violin, restored to playable condition, at the National Music Museum in Vermillion, South Dakota. (Portion of a photograph by Larry Jacobsen, via Wikimedia Commons.) |

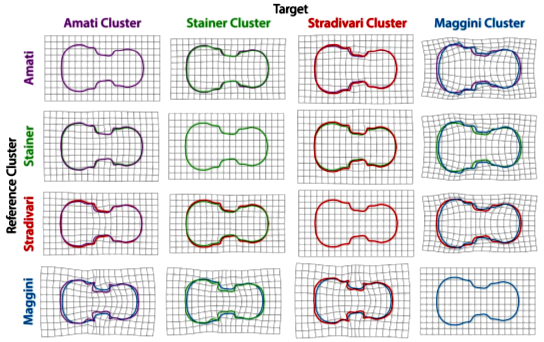

"There are many parallels between leaves and violins... Both have beautiful shapes that are potentially functional, change over time, or result from mimicry. Shape is information that can tell us a story. Just as evolutionary changes in leaf shape inform us about mechanisms that ultimately determine plant morphology, the analysis of cultural innovations, such as violins, gives us a glimpse into the historical forces shaping our lives and creativity."[6]Chitwood built a dataset of the shape of more than 9,000 violins, built over the course of 400 years, from auction house images.[5-6] Among the luthiers represented were Giovanni Paolo Maggini, Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù, and Antonio Stradivari. There were also luthiers who copied Stradivari. These were Nicolas Lupot, Vincenzo Panormo, and Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume.[6] Chitwood's linear discriminant analysis corroborated historical accounts of who copied whom. The analysis also demonstrated that four discrete shapes predominated in most instruments and the widespread imitation and the transmission of design (see figure).[5] Says Chitwood, “This is a fantastic example of how advances in one field can help advance a seemingly unrelated field."[6]

|

| Thin plate splines of major violin clusters. The differences have been amplified by a factor of four for better visualization. (Fig. 7 of ref. 5.)[5] |

References:

- Matthew W. Tocheri, Caley M. Orr, Marc C. Jacofsky, and Mary W. Marzke, "The Evolutionary History of the Hominin Hand since the Last Common Ancestor of Pan and Homo," Journal of Anatomy, vol. 212, no. 4 (April, 2008), pp. 544-562. A PDF file is available here.

- Irving Wladawsky-Berger, "The Co-Evolution of Humans and our Tools," Irving Wladawsky-Berger Blog, March 7, 2011.

- Academy Of Ancient Music Web Site.

- 1 - Hour of Early Middle Ages Music, YouTube Video.

- Daniel H. Chitwood, "Imitation, Genetic Lineages, and Time Influenced the Morphological Evolution of the Violin," PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 10 (October 8, 2014), Document No. e109229, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109229. This is an Open Access Publication with a PDF file available here.

- Plant scientist discovers basis of evolution in violins, Donald Danforth Plant Science Center Press Release, October 8, 2014.