Terracotta Army

August 29, 2014

There was a lot of

human history before the advent of the systematic practice of

chemistry. In this pre-chemistry period, humans used

natural materials for most of the things for which we use

synthetic materials. One ancient example of such a material is

Tyrian purple, also known as royal purple. This

natural dye, which is an extract from the

sea snail,

Bolinus brandaris, was expensive; thus, the "royal" appellation.

Even today, some natural materials have

properties that are difficult to replicate. I was reminded of that when I was doing

research on

superconductivity early in my

career. In those days before

high temperature superconductors, all superconductivity

experiments were done using

liquid helium.

We used so much liquid helium that we had our own machine for

helium liquefaction. The

technician who was responsible for running the machine showed me some of the

washers used in the machine. These were made from natural

leather, since the material functioned well at low

temperatures.

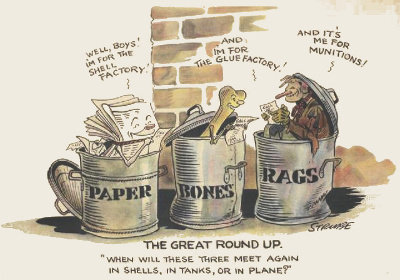

One common

human activity is

gluing things together. In the days before

polyvinyl acetate-based

Elmer's Glue and my favorite,

five-minute epoxy,

animal glue was used. Animal glue is produced by

boiling animal connective tissue, such as

skins,

bones, and

hides, in

water to induce

hydrolysis of their contained

collagen.

Since older

horses were in good supply in the days before

motorized vehicles, the appropriate parts of horses were mostly used; thus, the expression, "off to the glue factory." Although the principal use of the best quality glue,

hide glue, was in

woodworking, it was also used as a

binder for

paints and

inks.

Hide glue has quite a few excellent properties. It can be stored as dried flakes, or sheets, that are turned into the glue by dissolving in 140°

F (60°

C) water. It sets rather quickly, within a few

minutes,a glued

joint can be heated for release, and it

adheres to itself, which is something that a polyvinyl acetate glue won't do. Its

surface tension allows an automatic alignment of parts, which is useful in the construction of precision woodworks, such as

violins.

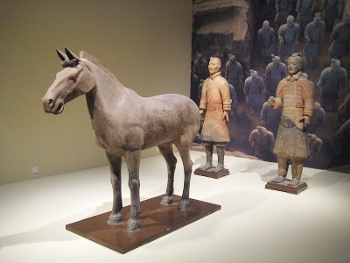

The

Chinese World Heritage Site, The

Mausoleum of the

First Qin Emperor, is familiar to most people by its collection of

sculptures known as the

Terracotta Army, discovered in 1974. There are a myriad of human figures, mostly

soldiers, buried there, along with figures of horses,

chariots, and a small number of other things. As can be expected, the

government of China has devoted considerable resources to the Army's preservation, and to research on the figures.

Qin Shihuang, who was China's First Emperor, had this underground

palace complex created as a duplicate of his palace in

Xianyang in 221

BC.[1-2] His imperial

guard was replicated in full

armor and in fine detail. The sculptured figures, along with their horses, chariots and

weapons, are all different. They document this period in history, and also the craft and techniques of

potters and

bronze-workers of the time.[2]

As can be seen in the photographs, this is an impressive work of

art, but it was more impressive at the time of its conception, since the statuary was actually

painted to closely represent the subjects. The burial in damp

soil has eradicated nearly all traces of the

pigments. Now, Chinese

scholars from the Key Scientific Research Base of Ancient Polychrome Pottery Conservation of the

State Administration for Cultural Heritage have done an analysis of the pigment traces and found that the sculptures were coated first with a non-pigmented

lacquer that was overcoated with polychrome layers. Animal glue was used as the binding medium of the polychrome layers.[1-2]

The base coat for the polychrome layers was one, or two, layers of an

East Asian lacquer obtained from

lacquer trees. The polychrome pigments included

cinnabar (

HgS),

apatite (

Ca5(

PO4)

3OH),

azurite (

Cu3(

CO3)

2(OH)

2) and

malachite (Cu

2CO

3(OH)

2).[2]

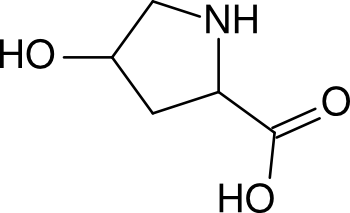

Although extremely low levels the

proteinaceous binding medium survived immersion in water-saturated

loess for more than two

millennia, the research team was able to identify the medium using

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS).[1] This technique provides high sensitivity with only minimal sample pretreatment.[2] Extracted

proteins were complexed with

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), subjected to

dialysis, then

hydrolyzed with high purity

trypsin to generate

peptide fragments.[2] The peptide fragments identified the binder as an animal glue.

Scientists commonly

double-check their findings to ensure that they're not somehow fooling themselves. The Chinese research team prepared their own version of terracotta coated using the materials discovered in the analysis. The glues tested included an adhesive formulated from the

eggs of

free-range chickens. These model samples were buried in one

meter of loess soil for one year, and the model analysis gave the same results as the Terracotta Army colorants.[2] This research was

funded by the National Key Technology R&D Program, China, grant no. 2010BAK67B12.[2]

References:

- Hongtao Yan, Jingjing An, Tie Zhou, Yin Xia, and Bo Rong, "Identification of proteinaceous binding media for the polychrome terracotta army of Emperor Qin Shihuang by MALDI-TOF-MS," Chinese Science Bulletin, vol. 59, no. 21 (July, 2014), pp. 2574-2581.

- Scientists solve 2000-year-old mystery of the binding media in China's polychrome Terracotta Army, Press Release from Science China Press, August 1, 2014.