Silly Putty

August 6, 2014

There's a saying, "

Build a better mousetrap, and the world will beat a path to your door." This saying is a mélange of two

19th century quotations by

Ralph Waldo Emerson. The phrase is popular, since it's a paean to

innovation.

Inventors have heeded the call, since a search of the

US Patent and Trademark Office yields 187

patents from 1790 to the present with "mouse trap" or "mousetrap" in their title. Ninety-two of these were granted from 1976 to the present.

|

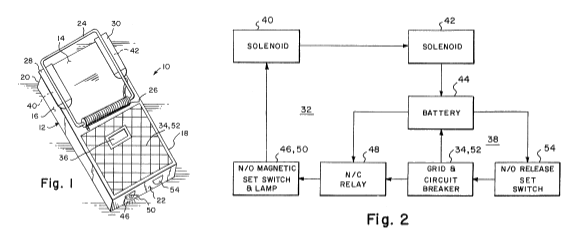

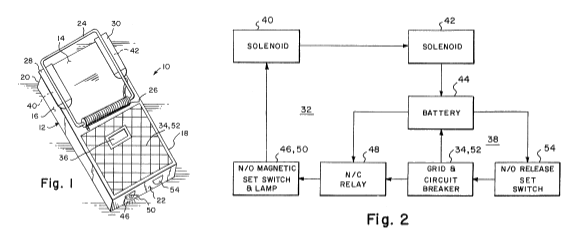

| Figures one and two from Donald W. Dufaux and George Spector, "Magnetic computerized mouse trap," US Patent No. 5,528,853, June 25, 1996. (Google Patents.)[1] |

Not all innovations are patent-worthy, since it's important to look at the

economics of practicing the invention. There's a considerable cost in prosecuting a patent application, the cost of

maintenance fees, and the possible cost of defending the patent against

infringers. In the mousetrap case, why would anyone want to buy your particularly effective mousetrap when they can buy a package of several conventional,

spring traps for a

dollar at many stores?

Some patented inventions make a lot of money.

Chester Carlson's invention of

xerography is one example.[2] I wrote about Carlson and his invention in a

previous article (PARC Turns Forty, September 28, 2010). A more recent example is

Pfizer's cholesterol-lowering

drug,

Lipitor. Lipitor's 1993 patent, which expired in 2011, resulted in more than $100 billion in

revenue for Pfizer. The Lipitor patent is considered to have been the most lucrative patent.[3]

Most companies don't rely on just a single patent to protect their product line. They're constantly patenting improvements, or possible alternatives to what they

manufacture. They sometimes

license these in a package to other companies, such

patent portfolios increasing the value of fundamental patents with added fortification against infringers.

About a

decade ago,

NTP, Inc. was able to extract a $612.5 million payment from Research in Motion (now,

BlackBerry Limited, manufacturer of the

BlackBerry) for infringing its patents on a

wireless email system. The settlement came only after protracted

litigation, which, as I mentioned earlier, is another cost center for patents.

As

scientists will admit, failures in the

laboratory sometimes turn into unexpected successes. This is often the case when a failed

industrial process becomes a

consumer product. One example of this was the early attempt by

American scientist,

Thomas Adams (1818-1905), to use

chicle, the

natural gum of

Manilkara trees, as a replacement for

rubber. Instead, he went on to invent

chewing gum.

Sculpey is a popular

polymer clay used for

sculpting by

Children and

artists. It has the desirable

property that it's soft, and easily worked, but it can be hardened in a low

temperature oven. The Sculpey

composition was originally intended as a

thermal transfer compound, since it could be

formulated to contain a high proportion of

thermally conducting fillers. A composition similar to Sculpey contains the following:[4]

Polyvinylchloride, 5 - 95 weight-%

Phthalate-free softener, 5 - 30 weight-%

Stabiliser, 0 - 10 weight-%

Co-stabiliser, 0 - 10 weight-%

Fillers, 0 - 75 weight-%

Colorant, 0 - 5 weight-%

Other additives, 0 - 5 weight-%

Play-Doh is another popular children's modeling compound originally manufactured for another purpose; namely, a

wallpaper cleaner. The original formulation was

wheat flour,

water,

salt,

boric acid, and

mineral oil. A modern composition is as follows:[5]

Sodium chloride, 3% to ~10%

Calcium chloride, ~3% to ~10%

Aluminum sulfate, ~0.5% to ~1.1%

10 molar borax decahydrate, ~0.35% to ~0.80%

Sodium benzoate, ~0.1% to ~0.5%

Wheat flour,~30% to ~38%

Waxy corn starch, ~3.5% to ~7.0%

Polyethylene glycol (PEG 1500) monostearate, ~0.4% to ~1.0%

Mineral oil, ~2.5% to ~4.0%

Vanilla fragrance, ~0.05% to ~0.25%

Water, balance (~45%)

In this composition, the amounts of aluminum sulfate and borax decahydrate are adjusted to give a

pH in the range of about 3.5 to about 4.5. Now you know that the Play-Doh smell is vanilla. The composition can be

pigmented.

Silly Putty is another example of a failed rubber substitute becoming a popular consumer play item. The Silly Putty

trademark is owned by

Crayola, but there are similar materials sold under different names. That's because the original research goes back to

World War II, when the

US was looking for alternative rubber materials.

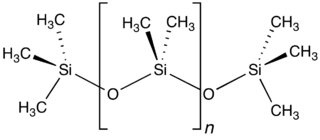

The original starting composition was just

polydimethylsiloxane, [C

2H

6OSi]

n, a

silicone oil, reacted with

boric acid.[6-7] The unusual

mechanical characteristic of this material is that it can be slowly worked, like a clay, but it behaves as an

elastic solid when the

rate of applied

force is large. This characteristic is a result of the

viscoelasticity of the polydimethylsiloxane.

According to

Wikipedia, this is the composition of Silly Putty:

Dimethyl siloxane polymer, terminated with boric acid, 65%

Silica (crystalline quartz), 17%

Thixatrol ST (castor oil derivative), 9%

Polydimethylsiloxane, 4%

Decamethyl cyclopentasiloxane, 1%

Glycerine, 1%

Titanium dioxide, 1%

Over the years, inventors have developed improved compositions.[8] More than four thousand

tons of Silly Putty have been sold since 1950.[9] The package size is 0.46

ounce (13

grams); so, doing the

math, more than 278 million units have been sold.

References:

- Donald W. Dufaux and George Spector, "Magnetic computerized mouse trap," US Patent No. 5,528,853, June 25, 1996.

- Chester F. Carlson, "electrophotography," US Patent No. 2,297,691 (October 6, 1942).

-

Bruce D. Roth, "[R-(R*R*)]-2-(4-fluorophenyl)-β,δ-dihydroxy-5-(1-methylethyl-3-phenyl-4-[(phenylamino) carbonyl]- 1H-pyrrole-1-heptanoic acid, its lactone form and salts thereof," US Patent No. 5,273,995, December 28, 1993.

- Yvette Freese, Ingrid Reutter, and Heinrich Schnorrer, "Modeling composition and its use," European Patent No. EP1957572, October 26, 2011.

- Linwood E. Doane, Jr., and Lev Tsimberg, "Starch-based modeling compound," US Patent No. 6,713,624, March 30, 2004.

- Mcgregor Rob Roy and Warrick Earl Leathen, "Treating dimethyl silicone polymer with boric oxide," US Patent No. 2,431,878, December 2, 1947.

- James G E Wright, "Process for making puttylike elastic plastic, siloxane derivative composition containing zinc hydroxide," US Patent No. 2,541,851, Feb 13, 1951.

- Maurice A. Minuto, "Method of Making Bouncing Silicone Putty-Like Compositions," US Patent No. 4371493, February 1, 1983.

- Eugene S. Robinson, "How That Pinkish Goo Called Silly Putty Came Out Of Its Shell," NPR, July 17, 2014.