Trust in Science

October 13, 2014 Who Do You Trust? was a television game show that ran from 1957-1963. I'm sure that early in the show's planning, someone pointed out that the title should be, Whom Do You Trust?, and he was promptly laughed out of the room. Such was the fate of the Grammar Police even before the Internet. Trust is an essential part of science. Aside from the few reported problems of data fabrication and plagiarism that seem to happen on a near weekly basis, scientists are an honest bunch, at least percentage-wise. Perhaps it's my physical science hubris speaking, but nearly all such dishonesty seems to happen in the biological and social sciences, and in psychology. One egregious counterexample is the Schön scandal in physics, so no field of science is without sin. We're living is an era of elevated distrust. The public seems to have lost trust in corporate and financial institutions, and in their government leaders. While U.S. President, Dwight D. Eisenhower, rightly warned us in 1961 about the danger of the military-industrial complex, who in the new millennium warned us about the insidious affect of lobbyists, political action committees, and money on government policy? | In God We Trust - All Others Pay Cash. In God We Trust (shown on a twenty dollar bill) is the modern motto of the United States, substituting for e pluribus unum. (Via Wikimedia Commons.) |

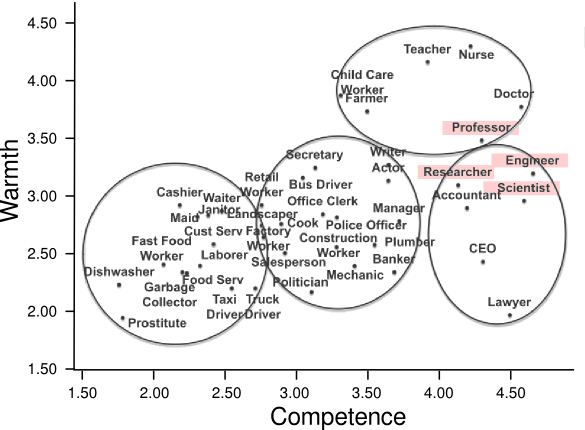

Scientists are idiotsThe Internet, apparently, has a strong bias against scientists. While I object to being called an idiot and a liar, I do confess that I'm a liberal. In my experience, most scientists are liberals, so that's not a surprise. It's also my experience that most engineers are conservatives. It's probably good to have conservatives design things like elevators and airliners, so a conservative engineer is a good thing. Likewise, there shouldn't anything too damning about being a liberal. Susan Fiske and Cydney Dupree of Princeton University's Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs have just published a study of the public perception of scientists, and they make recommendations as to how this perception might be improved. According to Fiske and Dupree, the public perception of a person is a combination of a their apparent intent (warmth) and capability (competence).[1-2] Their work, which involved just the American perception of scientists, was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.[2] According to their study, scientists are considered to be competent, but they lack public trust, since they are not friendly or warm. They advise scientists to act "warmer."[2] Says lead author, Susan Fiske, the Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology at Princeton, and professor of public affairs,

Scientists are liars

Scientists are liberal

"Scientists have earned the respect of Americans but not necessarily their trust... but this gap can be filled by showing concern for humanity and the environment. Rather than persuading, scientists may better serve citizens by discussing, teaching and sharing information to convey trustworthy intentions."[2]The study involved a first phase in which a list of 42 typical American jobs was compiled by an online survey (I would have used government statistics, but the psychology modus operandi is the survey). The list included scientists, researchers, professors and teachers.[1-2] Another group of adults was polled to rate these professions for warmth and competence. The results are summarized in the figure.[2]

|

| Warmth-Confidence plot for professions, as found in the described study by Fiske and Dupree. (Princeton University image, redrawn for clarity.)[2] |

References:

- Susan T. Fiske and Cydney Dupree, "Gaining trust as well as respect in communicating to motivated audiences about science topics," Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 111, supplement 4 (September 16, 2014), pp. 13593-13597.

- B. Rose Huber, "Scientists Seen as Competent But Not Trusted by Americans," Princeton University Press Release, September 22, 2014