Road Salt

December 1, 2014

I've been in

Buffalo, New York, once, on business at the regional offices of the

Federal Communications Commission. This was in the

warmer months, and it included a pleasant excursion to nearby

Niagara Falls, the locale of the 1953

Marilyn Monroe film, "

Niagara."[1] It was also the setting for the enjoyable, but short-lived, 2004

television series,

Wonderfalls.[2] In the past, Niagara Falls was promoted as a

honeymoon destination, and it's interesting how

Viagra rhymes with Niagara.

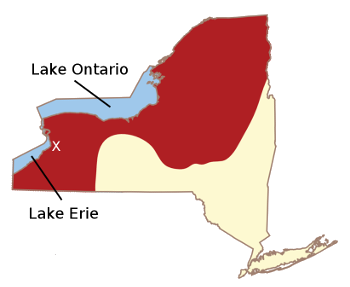

Buffalo gained national attention in mid-November, 2014, after being buried under a huge

snowfall. Buffalo is no stranger to snow, since its proximity to the

Great Lakes leads to considerable quantities of

lake-effect snow. Lake-effect snow occurs when

eastwardly winds draw

moisture from above the lakes and

precipitates this as

snow. Most of

Upstate New York experiences lake-effect snow, as shown in the figure.

Since

humans don't

hibernate in

winter, people in Buffalo and quite a few other places, just push the snow out of the way and get on with their lives. In

Manhattan, and similar places where there are aren't enough places to hold the snow, the snow is scooped into

melters and put into the

storm sewers where it would have gone eventually. Even when a

roadway is nicely

plowed, some of the slippery stuff still remains, and that's when

chemical snow removal comes into play.

Rock salt, also known as

halite, is the traditional method of mitigation for small quantities of snow. It's an inexpensive

chemical, and it's relatively benign since we use it to

season our

food. One

taste of my

morning oatmeal,

cooked by the "old fashioned" method of

boiling in a

pan on the

stove, instantly informs me that I've forgotten to salt the

water. Salt has been reviled as being bad for your

health, but a little pinch of salt goes a long way in making some foods palatable. Some people add a little salt to their

coffee to reduce

bitterness, a procedure that actually has a

scientific basis.[3-4]

Mixtures of

materials will generally have a lower

melting/freezing point than the

pure substances, as the example of

lead-tin solder shows.

Lead has a melting point of 327.5 °C, and

tin has a melting point of 232 °C, but the common 63% lead/37% tin solder has a melting point of just 183 °C. This same freezing point reduction happens when we add salt to water, and the freezing point can be reduced as low as -18 °C. Salt

corrodes both

metal and

concrete. I wrote about salt corrosion of concrete in a

previous article (Salt Corrosion, October 1, 2014).

If there's a need to prevent freezing, or promote thawing, at lower temperatures, other

ionic solids, such as

magnesium chloride (MgCl

2),

calcium chloride (CaCl

2), or

potassium chloride (KCl) can be used. Ionic solids will

dissociate into multiple

ions in water, and this has an advantage. The

van't Hoff factor is the enhancement of the

freezing point depression that arises from this dissociation. While

non-electrolytes will have a van't Hoff factor of about 1,

electrolytes will have a factor roughly equal to the number of ions the electrolyte forms in solution. For this reason, (MgCl

2) and calcium chloride (CaCl

2) have more "

bang-for-the-buck" when used to melt ice.

Other compounds are used for ice-melting, and

airports use various

non-flammable glycols, such as

propylene glycol, to

deice aircraft. Like table salt, propylene glycol is a

food additive, so it's generally regarded as safe.

Scientists, however, are always looking to advance the

status quo, and what better place to conduct

research on chemical deicers than

Washington State, which experiences

weather extremes conducive to icy roadways. In Washington state, about four

tons of salt are used per

lane mile in winter road

maintenance.[5] In

Minnesota, nine tons of salt per lane mile are used.[5]

One motivation for such research is that road salt in Washington and other

northern states is in short supply this season, and there have been

price increases of up to 30%. Another is that heavy salt use is damaging to the

environment.[5] The

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reported alarming levels of

sodium and

chlorine in

groundwater for

states in the

Eastern United States in 2013, and high salt levels can affect

potable water supplies.[5]

Winter maintenance of roadways is big business in the US, with $2.3 billion spent each year for removal of highway snow and ice, plus another $5 billion in hidden associated costs.[5] Hidden costs include the environmental impact of

sand, salt, and other chemical deicers, and corrosion of the roadways and

motor vehicles.[5]

Washington State University is part of a recently established a

Center for Environmentally Sustainable Transportation in Cold Climates that's the only center of its type in the

United States. The center has received

funding of $2.8 million over two years from the

US Department of Transportation. Aside from Washington State, the center's participants include the

University of Alaska Fairbanks and

Montana State University.[5] Says

Xianming Shi,

associate professor in

Civil and Environmental Engineering at Washington State and assistant director of the center,

"We are kind of salt addicted, like with petroleum, as it's been so cheap and convenient for the last 50 years... With a four-lane highway, you have 16 tons of salt per year in that one mile segment... In 50 years, that's about 800 tons of salt in that one mile – and 99 percent of it stays in the environment. It doesn't degrade. It's a scary picture."[5]

Snow and ice control are simple operations, but they require quite a bit of operator judgment. Salt needs to be applied in a proper quantity for the conditions, but the amount is judged

visually. Says Shi, "By the time you can see salt on the road, it's way too much and is going into the

vegetation and groundwater."[5] One of Shi's research areas is "smart snowplow"

technology in which snowplows have integrated

sensors that read

pavement temperature, salt left from previous applications, the presence of ice, and the amount of road

friction.[5]

As an advocate of

open source software, I'm happy to see that the

Federal Highway Administration has developed the Maintenance Decision Support System, an open source tool that suggests salt application rates based on road and weather conditions.[5] Shi has also been investigating alternative, less corrosive deicers, such as

beet and

tomato juice, and

barley residue from

vodka distilleries.[5]

As a complement to this research, Shi is investigating deicer-resistant concrete that also incorporates

nanoscale, and larger, particles that produce a

surface barrier to prevent

bonding with snow and ice. This makes plowing easier, and it decreases the need for salt. Such improvements are useful not just for roadways, but for

sidewalks and

parking lots.[5] Shi presented his approaches to winter roadway maintenance at the

American Public Works Association Western Snow and Ice Conference in September.[5]

References:

- Niagara (1953, Henry Hathaway, Director) on the Internet Movie Database.

- Wonderfalls (2004, Television Series, Bryan Fuller, Creator) on the Internet Movie Database.

- P. A. S. Breslin and G. K. Beauchamp, "Salt enhances flavour by suppressing bitterness," Nature, vol. 387, no. 6633 (June 5, 1997), pp. 563 ff., doi:10.1038/42388.

- Russell Keast, Paul Breslin and Gary Beauchamp, "Suppression of bitterness using sodium salts," Chimia: International journal for chemistry, vol. 55, no. 5 (2001), pp. 441-447.

- Rebecca Phillips, "Green highway snow and ice control cuts the chemicals," Washington State University Press Release, November 19, 2014.