Radio Detectors

March 28, 2014

German physicist,

Heinrich Hertz (1857-1894), demonstrated the

transmission and

reception of

radio waves in 1887. In his

experiments, he used a

spark gap as a generator of radio waves, and he detected the

electromagnetic radiation when it induced

sparks in another gap connected to an

antenna. When Hertz turned the spark

voltage supply on and off, it was a primitive form of

modulation called on-off keying.

In the

twentieth century, when the generation and reception of radio waves became more manageable, other modulation types were invented. With today's

digital communication technology, there are too many modulation schemes to list in an article like this. Possibly the most important type to most people is

quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM), used in

wireless local area networks.

The

US Federal Communications Commission once listed the basic modulation types shown in the table, where "A" signifies

amplitude modulation, and "F" signifies

frequency modulation. This was the list I needed to memorize when I took the

exam for my

commercial radiotelephone operator license in the

1960s.

| Type | Description |

| A0 | Unmodulated |

| A1 | On-Off Telegraphy |

| A2 | Amplitude Modulated Telegraphy |

| A3 | Telephony ("AM Radio") |

| A4 | Facsimile |

| A5 | Television |

| F0 | Unmodulated |

| F1 | Frequency Shift Telegraphy |

| F2 | Frequency Modulated Telegraphy |

| F3 | Telephony ("FM Radio") |

| F4 | Facsimile |

| F5 | Television |

Before

Edwin Armstrong invented

frequency modulation in 1933, all modulated radio was amplitude modulated. Simple devices, such as the

Branly coherer, were used as early detectors of radiotelegraphy (A1 in the above table), but they weren't capable of detecting speech signals (radiotelephony). For that, you needed a

rectifier, and the first such rectifiers were the simple "

cat's whisker"

semiconductor diodes shown in the figure.

After a while,

vacuum tube rectifiers became the radio detectors of choice, since they didn't need as much attention as a cat's whisker diode. Today, there's a wide variety of

semiconductor diode types available, priced as low as a few cents per piece.

The diode detector is sufficient for most applications, but other radio detection tasks, such as those in

radio astronomy and

medical imaging (

MRI), require better

sensitivity.

Scientists at the

Niels Bohr Institute of the

University of Copenhagen (Copenhagen, Denmark) have teamed with

colleagues at the

Technical University of Denmark (Kongens Lyngby, Denmark) and the

Joint Quantum Institute, a joint operation of the

National Institute of Standards and Technology and the

University of Maryland (College Park, Maryland) to create an

optomechanical radio detector.[2-5]

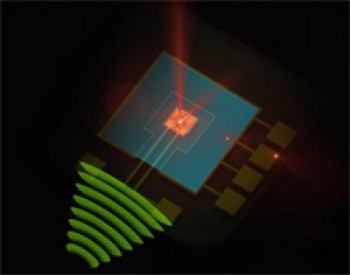

The detector is based on the fact that

nanomechanical oscillators will couple strongly to

microwave and

optical fields.[2] The device is essentially an

upconverter that translates radio frequencies to light frequencies, so a

megahertz radio signal is converted to hundreds of

terahertz.[5] This allows signal detection using

quantum optical techniques used in quantum-limited signal detection.[2]

The usual way to reduce

noise in a detector is to eliminate

thermal noise by cooling to

liquid helium temperatures. Such temperatures, although very low, still allow some thermal noise. Says

Eugene Polzik, head of the

Quantum Optics Research Center at the Niels Bohr Institute,

"We have developed a detector that does not need to be cooled down, but which can operate at room temperature and yet hardly has any thermal noise. The only noise that fundamentally remains is so-called quantum noise, which is the minimal fluctuations of the laser light itself."[4]

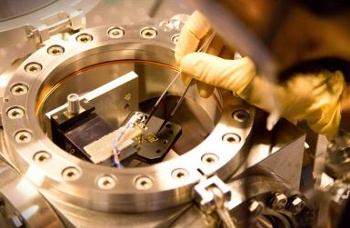

The device has an antenna that couples radio signals to an

aluminum-coated 50

nanometer thickness membrane formed from

silicon nitride. The membrane is one plate of a capacitor. Although the device is isolated in a

vacuum chamber (see figure), it's not cooled. The thermal noise is reduced by the thinness of the membrane. A

bias voltage of less than ten

volts is enough to induce strong coupling between the radio-frequency voltage and the membrane's displacement.[2]

Optical coupling is made by

reflecting a

laser from the membrane surface.[2] The radio and light waves interact

non-linearly with the mechanical resonance of the membrane.[2,4] The radio signals can then be detected as an optical

phase shift with quantum-limited sensitivity.[2] The

noise equivalent temperature is just 40

mK, and the detector sensitivity limit is 5

pV per

square-root hertz.[2]

As Polzik summarizes,

"This membrane is an extremely good oscillator and that is why it is so ultrasensitive. At room temperature, it works as effectively as if it was cooled down to minus 271°C, and we are working to get it even closer to minus 273 degrees C, which is the absolute minimum. In addition, it is a huge advantage to use optical detection, as instead of using ordinary copper wires to transmit the signal, you can use fiber optic cables, where there is no energy loss."[4]

References:

- Edwin H. Armstrong, "Radio signaling system," US Patent No. 1,941,066, December 26, 1933.

- T. Bagci, A. Simonsen, S. Schmid, L. G. Villanueva, E. Zeuthen, J. Appel, J. M. Taylor, A. Sørensen, K. Usami, A. Schliesser and E. S. Polzik, "Optical detection of radio waves through a nanomechanical transducer," Nature, vol. 507, no. 7490 (March 6, 2014), pp. 81-85.

- Mika A. Sillanpää and Pertti J. Hakonen, "Optomechanics: Hardware for a quantum network," Nature, vol. 507, no. 7490 (March 6, 2014), pp. 45-46.

- Ultra sensitive detection of radio waves with lasers, Niels Bohr Institute Press Release, March 5, 2014.

- Up-Converted Radio - The way to treat radio waves in a noisy environment is to turn them into visible light, Joint Quatum Institute Press Release, March 6, 2014