Phonon Noise

December 17, 2014

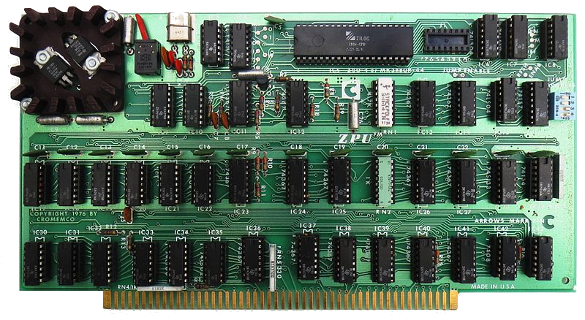

I had an

early buy-in to

personal computing. A few years before the

Apple Computer and the

IBM PC, whose introduction most people identify with the start of personal computing, there was

S-100 bus hardware and

CP/M software. My

computers at

home and at the

laboratory were built from

component cards plugged into an S-100

backplane, named for the simple reason that there were 100 card edge

contacts, fifty to a side.

Those early days were also the days of

impact printers. Eventually, I obtained a

Diablo daisy wheel printer to print

data files and

drafts of

scientific papers and

reports. Although this printer would quickly print entire files at one time, it would also print a single

character at a time in a tip-tap

rhythm reminiscent of a

typewriter. On one slow day, probably while waiting for some

experiment to finish, I had the idea to use the computer to

simulate a person's typing at a typewriter.

Having the computer send a stream of evenly-spaced characters at ten

words per minute wouldn't be a good simulation. People do not type that regularly; instead, they type in fits, sometimes faster, sometimes slower. My computer simulated typing more convincingly through use of

1/F noise (one-over-F noise). 1/F noise, which is often called "pink noise," is one type of

noise that

electronic component designers have been fighting for

decades.

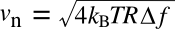

The first discovered

electronic noise was

Johnson-Nyquist noise, found in experiments by

John B. Johnson in 1926, and explained by his

Bell Labs colleague,

Harry Nyquist, in back-to-back

papers in the

Physical Review.[1-2] This

voltage noise, present across any

resistor at any

temperature above

absolute zero, is given as,

where

vn is the

root-mean-square (rms) noise voltage,

kB is the

Boltzmann constant (1.3806 x 10

−23 joule/

kelvin),

R is the

resistance (

ohms),

T is the absolute temperature (kelvin), and

Δf is the

frequency interval over which the noise voltage is measured (

hertz). This noise doesn't depend on where the frequency interval is taken, so it's

frequency-independent noise, often called "

white noise." It can be called 1/F

0 noise, since taking frequency to the zero

power yields one. Most

radio frequency connections are made at fifty ohms; and, for that

source impedance, there's a

nanovolt of noise in every hertz

bandwidth at

room temperature.

One-over-F noise is different from white noise, since it increases at lower frequencies. If you look at a noise source on an

oscilloscope, you'll see the overall "fuzz" caused by white noise, but this white noise will ride atop a wandering baseline of 1/F noise. This noise was first discovered in

vacuum tubes, but it's found in all electronics, and even other

physical systems. In

semiconductor devices, it's generally caused by

defects at

material interfaces where

electrons and

holes are

randomly captured and released. It's not important at higher frequencies, and there's a "corner frequency" defined as the point where the pink and white noise components are equal.

As the above thermal noise

equation expresses, if you want lower noise, you need to go to lower temperature. That's why sensitive

amplifiers for many experiments are cooled to

cryogenic temperatures. Now, an international team of

scientists from

Chalmers University of Technology (Gothenburg, Sweden), the

Universidad de Salamanca (Salamanca, Spain), the

Low Noise Factory AB (Mölndal, Sweden), and the

California Institute of Technology (Pasadena, California) has found that there's a thermal noise at low temperatures that can't be removed. That's a noise caused by self-heating at cryogenic temperatures.[3-5]

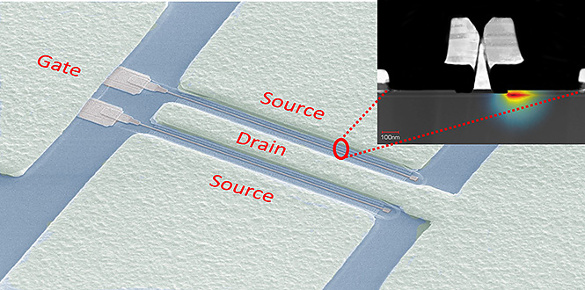

Microwave amplifiers operating at low temperature are important in

radio astronomy, and they enabled observations of the

cosmic microwave background radiation. The amplifiers are

transistorized low-noise amplifiers, and scientists at Chalmers University of Technology and a Chalmers spin-off, the Low Noise Factory, are developing optimized

indium phosphide transistors for low noise amplification. As

Jan Grahn, a

professor of

microwave technology at Chalmers, says,

"Cooling the amplifier modules to -260 degrees Celsius enables them to operate with the highest signal-to-noise ratio possible today... These advanced cryogenic amplifiers are of tremendous significance for signal detection in many areas of science, ranging from quantum computers to radio astronomy.”[5]

When these amplifiers were cooled to just a tenth of a degree above

absolute zero (-273° Celsius), it was expected that the only noise would be that associated with so-called "

hot electrons." Instead, it was found that self-heating of the transistors was a problem, since the mechanism for

heat transfer in

solids, the

phonons, are not that effective at such low temperatures.[3-5]

At about 20 kelvin, the high

energy phonons that are most efficient at transporting heat are absent, so only low energy phonons are there to transfer heat. Says

Austin Minnich , an

assistant professor in

Caltech's Division of Engineering and Applied Science and an

author of the study, "As a result, the transistor heats up until the temperature has increased enough that high-energy phonons become available again."[4]

Although this type of noise had been known for many years, its importance at very low temperatures wasn't realized. A chance meeting at Caltech between

Joel Schleeh, first author of the study and a

postdoc at Chalmers, and Minnich launched the research project. Schleeh was seeing more noise than he thought he should in such amplifiers, and conversation with Minnich connected this finding with phonons.[4]

One thing about noise, everyone wants to get rid of it, and this research has suggested some possibilities for doing this. The transistor design could be changed to allow phonons to operate in a larger

volume. Says Minnisch, "If you can make the phonon generation more spread out, then in principle you could reduce the temperature rise that occurs."[4] The research was funded by the

Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems (Vinnova), the

National Science Foundation, and a Caltech

start-up fund.[4-5]

References:

- J. B. Johnson, "Thermal Agitation of Electricity in Conductors," Phys. Rev., vol. 32 (July 1, 1928), pp. 97ff..

- H. Nyquis, "Thermal Agitation of Electric Charge in Conductors," Phys. Rev., vol. 32 (July 1, 1928), pp. 110ff..

- J. Schleeh, J. Mateos, I. Íñiguez-de-la-Torre, N. Wadefalk, P. A. Nilsson, J. Grahn, and A. J. Minnich, "Phonon black-body radiation limit for heat dissipation in electronics," Nature Materials (advance online publication, November 10, 2014), doi:10.1038/nmat4126.

- Ker Than, "Heat Transfer Sets the Noise Floor for Ultrasensitive Electronics," California Institute of Technology Press Release, November 10, 2014.

- Noise in a microwave amplifier is limited by quantum particles of heat, Chalmers University of Technology Press Release, November 10, 2014.