Nickel Hair

August 18, 2014 Folk wisdom gave about the same results as medical science until a few hundred years ago. The use of herbs to treat disease goes back three millennia, and some of the proposed treatments are strange. One working concept was Similia Similibus Curantur ("Like cures like") that is the principle behind the contemporary expression, "hair of the dog." Hair of the dog, as practiced today, is to use an alcoholic beverage as a palliative for an alcoholic hangover. From what I've read, this isn't recommended, and it's also not recommended that you drink so much to have a hangover in the first place. As they say, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Hair of the dog apparently refers to the folk practice of putting a few hairs of the dog that bit you into the bite wound. How that came into practice sounds more like witchcraft than anything else, but the idea of Similia Similibus Curantur goes back at least as far as Aristophanes (446 BC - c. 386 BC). Although I haven't found the passage (it's a fairly long book), Aristophanes, in "The Deipnosophistae of Athenaeus," supposedly tells the tale of a man who, having been blinded by thorns, is cured by throwing himself back into the brier patch.[1] Aristophanes, as was his style, was poking fun at Similia Similibus Curantur. | Br'er Rabbit at the table. Br'er Rabbit's favorite hiding place was a brier patch. (Via Wikimedia Commons.)[2] |

| Although powdered wigs were popular in his era, the young Isaac Newton (1642-1727) didn't appear to need

hair extensions in this portrait. (Via Wikimedia Commons.) |

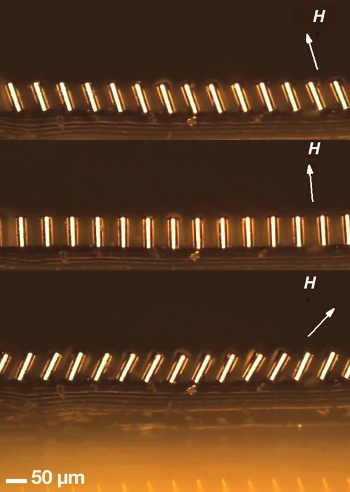

| Response of nickel hairs in a magnetic field. Because of a magnetic property called shape anisotropy, the hairs have a lower energy state when they are aligned parallel with the magnetic field. As can be seen in one image, the elastic mounting resists bending at too high an angle. (Screen captures from an MIT YouTube video.)[6] |

|

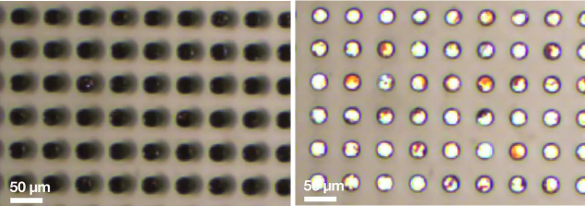

| Optical response of nickel hairs in a magnetic field. (Screen captures from an MIT YouTube video.)[6] |

"A nice thing about this substrate is that you can attach it to something with interesting contours... or, depending on how you design the magnetic field, you could get the pillars to close in like a flower. You could do a lot of things with the same platform."[5]This research was funded by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research.[4-5]

References:

- Aristophanes, "The Deipnosophistae of Athenaeus," from the Loeb Classical Library, 1930.

- Joel Chandler Harris, "Br'er Rabbit at the table from Uncle Remus, His Songs and His Sayings: The Folk-Lore of the Old Plantation," Illustrations by Frederick S. Church and James H. Moser, (D. Appleton and Company, New York), 1881.

- Iver E. Anderson, Frederick G. Yost, John F. Smith, Chad M. Miller and Robert L. Terpstra, "Pb-free Sn-Ag-Cu ternary eutectic solder, US Patent No. 5,527,628, June 18, 1996.

- Yangying Zhu, Dion S. Antao, Rong Xiao and Evelyn N. Wang, "Real-Time Manipulation with Magnetically Tunable Structures," Advanced Materials, Early View (July 22, 2014), DOI: 10.1002/adma.201401515.

- Jennifer Chu, "New material structures bend like microscopic hair," MIT Press Release, August 6, 2014.

- Melanie Gonick, "MIT engineers show their magnetic microhairs in action," Massachusetts Institute of Technology YouTube video, August 4, 2014.