The Man in the Moon's Missing Twin

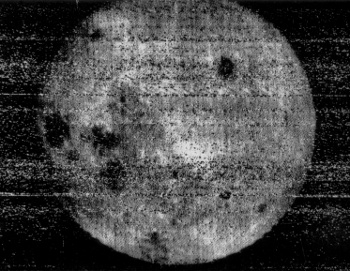

June 27, 2014 Most people, when they hear the term, "far side," think of the popular Far Side comic strip by Gary Larson. Larson stopped drawing the Far Side in 1995, but many of the strips are so memorable that they can be found now, twenty years later, in an Internet search. Of course, none of those images should be there, since these are copyrighted works. Larson has a web site at thefarside.com. There's another "far side," and that's the far side of the Moon. I wrote about the far side of the Moon in a previous article (Far Side of the Moon, February 6, 2012). Many people refer to it as the "dark side" of the Moon, since they think that it's always dark, when it actually gets about as much insolation, on average, as the side that's visible from the Earth. The side facing the Earth, however, gets a bit more light because of sunlight reflected from the Earth, a phenomenon called Earthshine. Because of Earthshine, the New Moon is never perfectly black. The darkness of the New Moon is actually a function of how much snow and reflecting clouds the Earth has at a given time. We only see one side of the Moon, since the Moon is tidally locked to the Earth. Until 1965, it was thought that the planet, Mercury, was tidally locked to the Sun; instead, it rotates three times for every two revolutions around the Sun, so it had appeared to be tidally locked in prior observations. Because of libration, a consequence of the slightly elliptical orbit of the Moon, and parallax, we can actually observe about 59% of the Moon's surface from Earth. Many men have walked on the Moon, but none have walked on the far side. In the early days of manned spaceflight, such an expedition would have been dangerous, since the bulk of the Moon would have blocked communication with Earth. Today, it's easy to put a communications satellites at the Moon to solve this problem. Still, we might still use the term, "dark side of the Moon," if by "dark" we mean an unexplored territory. Until 1959, there wasn't even an image of the Moon's far side. Finally, in October, 1959, the Soviet spacecraft, Luna 3, transmitted low resolution photographs of about 70% of the far side (see image). These images revealed a few large craters, as could have been expected. However, subsequent satellite reconnaissance in preparation for manned landing revealed some major differences between the Moon's near and far sides. | The first image of the far side of the moon, taken on October 7, 1959, by the Soviet Luna 3 spacecraft (North is up in this image). The Luna 3 images, low resolution though they were, were a sensation when they were published. (Via NASA Web Site). |

| Far side of the Moon. This NASA Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter composite image was made from more than 15,000 images acquired between November, 2009, and February, 2011. (NASA/Goddard/Arizona State University image.) |

| Equal time for the Woman of the Moon, Selene, the Moon goddess. The Roman god, Apollo, is also associated with the Moon, thus the eponymous Apollo Program, successful in landing the first humans on the Moon in July, 1969. (Oil on canvas painting, 1880, by Albert Aublet (1851-1938), via Wikimedia Commons.) |

References:

- Arpita Roy, Jason T. Wright and Steinn Sigurdsson, "Earthshine on a Young Moon: Explaining the Lunar Farside Highlands," The Astrophysical Journal Letters, vol. 788, no. 2 (June 9, 2014), doi:10.1088/2041-8205/788/2/L42.

- A'ndrea Elyse Messer, "55-year-old dark side of the moon mystery solved," Penn State University Press Release, June 9, 2014.