Graphene from Nickel

June 11, 2014

Most

materials solidify into

crystals, which are

regular arrays of atoms. That's a simple consequence of

thermodynamics, since such a regular arrangement of atoms is a low

entropy state; and, at least for

ions such as those of

sodium and

chlorine, such an arrangement leads to a higher

bonding energy between

atoms.

Essentially, you're minimizing the

Gibbs free energy G, which is a

function of both

reaction enthalpy (the bonding energy)

H and the entropy

S at a given

absolute temperature T; viz.,

G = H - TS.

In a perfect world, atoms would always arrange themselves in neat arrays, but in the real world, everything has

defects, and

atoms move around. Atoms will remain in placed at

absolute zero, essentially because atomic movement is

how temperature is defined. Atoms remain in place until about 80% of a material's

melting point in absolute temperature units (

kelvin). Above that, atom motion is used to beneficial effect in

annealing, which removes internal

strain.

The

industrial revolution was built not only by

steam, but also by

steel.

Iron is a plentiful and inexpensive material, and the 1855

Bessemer process, which had actually been practiced for quite a time before

Henry Bessemer's patent, allowed production of very pure iron in large quantity. Pure iron is soft and

ductile, but a pinch of

carbon transforms iron to

higher strength steel.

Carbon is a small atom (77

picometers (pm) when

bonded as sp3) compared with iron (126 pm), so carbon atoms are relatively mobile in iron. Since steel is such an important material, the

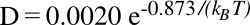

diffusion (movement) of carbon atoms in iron has been thoroughly researched. Carbon diffusion in iron follows an

Arrhenius-type law,

where

D is the

diffusion coefficient (measured in

cm2/

sec), the

activation energy is 0.873

electron volts,

kB is the

Boltzmann constant and

T is the

absolute temperature. Because of this is an

exponential function, the diffusion coefficient varies by many

orders of magnitude between

room temperature and the melting point of iron, 1538 °C.

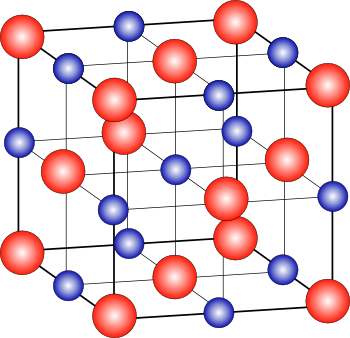

Nickel, like iron, is in the first

transition metal series of the

Periodic Table, and it's separated from iron by just one

chemical element,

cobalt. The crystal structure of nickel (

face-centered cubic) has its atoms more closely spaced than the

body-centered cubic structure of iron, so the diffusion of carbon in nickel is much smaller.

At high temperatures, the diffusivity of carbon in nickel is more than a million times smaller than that for iron.[1] However, if your goal is to transport carbon through a very thin layer of nickel, the diffusivity is more than enough. The

solubility of carbon in nickel is also a hundred times less than that of carbon in iron.[1]

Scientists from the

Department of Mechanical Engineering, the

University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, Michigan), the

Department of Mechanical Engineering, the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, Massachusetts), and

Guardian Industries Corporation (Carleton, Michigan) have used these properties of carbon in nickel to devise a process for production of large

area graphene sheets on

silica.[2-3]

The first process for creation of graphene was the use of

Scotch tape to exfoliate atomically thin graphene sheets from

graphite. It was a crude process, but it was good enough to win the 2010

Nobel Prize in Physics for its discoverers,

Andre Geim and

Konstantin Novoselov. It would be difficult to

commercialize graphene

devices using this technique.

Another process for production of graphene is to grow it on a

metal, such as nickel or

copper, but it's only useful when removed from the metal. Although the growth of large areas of graphene has become common, removal of the graphene from its growth

substrate is a major issue.[3] That's the problem tackled in this latest study.

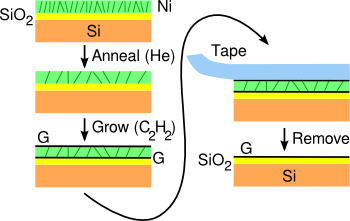

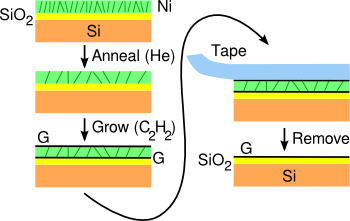

The

research team, led by

A. John Hart of MIT, developed a process for production of graphene on silica glass (SiO

2) by using

chemical vapor deposition (CVD) to grow graphene from

ethylene on both sides of a nickel film

deposited on the glass substrate. A subsequent dry

mechanical delamination using

adhesive tape removes the nickel layer and the top graphene layer to leave a layer of graphene on glass (see figure).[2]

| The graphene-on-glass process.

Graphene can be grown on both sides of a nickel film on a glass substrate.

(Original image by the study authors, redrawn for clarity, via MIT) |

The graphene is produced in

micrometer-sized,

monolayer to multiple-layer domains. There's greater than 90% coverage across a

centimeter dimension substrate, which was the size limit for their CVD system.[2] An important part of the removal process is a strain-relief anneal of the nickel film prior to graphene deposition. Although the nickel film remains adherent to the glass even after formation of the graphene, it can be mechanically removed after deposition.[2]

Says MIT's Hart,

"We still need to improve the uniformity and the quality of the graphene to make it useful... The ability to produce graphene directly on nonmetal substrates could be used for large-format displays and touch screens, and for 'smart' windows that have integrated devices like heaters and sensors."[3]

The work was supported by the

National Science Foundation, the

Air Force Office of Scientific Research, and Guardian Industries.[3]

References:

- J. J. Lander, H. E. Kern and A. L. Beach, "Solubility and Diffusion Coefficient of Carbon in Nickel: Reaction Rates of Nickel‐Carbon Alloys with Barium Oxide," J. Appl. Phys., vol. 23, no. 12 (December 1, 1052), p.1305ff., DOI:10.1063/1.1702064.

- Daniel Q. McNerny, B. Viswanath, Davor Copic, Fabrice R. Laye, Christophor Prohoda, Anna C. Brieland-Shoultz, Erik S. Polsen, Nicholas T. Dee, Vijayen S. Veerasamy and A. John Hart, "Direct fabrication of graphene on SiO2 enabled by thin film stress engineering," Scientific Reports, vol. 4 (May 23, 2014), Article no. 5049 (doi:10.1038/srep05049). This is an open access article with a PDF file available, here.

- David L. Chandler, "A new way to make sheets of graphene," MIT Press Release, May 23, 2014.