Fifty Years of BASIC

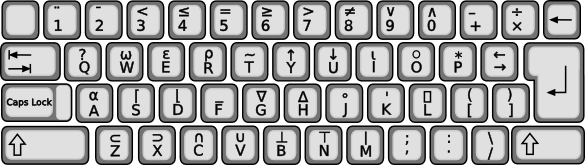

May 19, 2014 Fifty years ago, I was a high school student who had seen the many cinema versions of computers in science fiction films. As a member of the high school math club, I had seen a real computer, an IBM 1401, on a field trip to a local university. It certainly didn't look like the cinema computers, and about all it could do was play tic-tac-toe and calculate the day of the week on which you were born. While many of today's youth are writing computer programs in elementary school, members of my generation had never programmed at college age. Surprisingly, for someone who now writes a lot of code in several languages, I never took a computer course in college. The reason for this was my resistance to the gatekeeper computing paradigm of the time. To run a computer program, your FORTRAN code was punched into cards, which were placed in a box and passed to the "high priests" of the computer. They would eventually process your cards through a card reader, your code would be run by the computer, and you would get a printout. The printout was invariably a long list of error messages from some incorrect syntax; so, you would revise your card stack, and the process would continue. None of this appealed to me, nor was I motivated by seeing weary students hauling punch card boxes between classes. This may have resulted in the little known complaint of the period called "engineer's elbow." When I became a graduate student, the computer paradigm had changed, and I finally started to program. The change was the implementation of timeshare terminals for APL programming on an IBM 360. There were no punch cards, you wrote your source code as you would type any document, and there was instant feedback of syntax errors. The system also prevented the neophyte error of programming unintentional infinite loops, which happened to me on occasion. Now, I find "while(1)" to be a useful construct. APL was an interpreted language developed at IBM by computer scientist, Kenneth E. Iverson (1920-2004), who was the recipient of the Association for Computing Machinery's 1979 Turing Award. As can be seen from the keyboard layout, below, the mathematical notation was quite abstract, but it allowed complex operations to be done with a single line of code. |

| This is the layout of the IBM APL keyboard. I labored over this keyboard layout for many hours as a graduate student.(Via Wikimedia Commons.) |

| John Kemeny, co-creator of BASIC, in 1967. (Dartmouth College image.) |

| Tom Kurtz, co-creator of BASIC. (Dartmouth College image by Adrian N. Bouchard, courtesy of Rauner Special Collections Library.) |

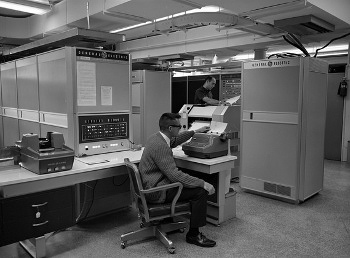

| General Electric 225 computer at Dartmouth College, 1964. (Dartmouth College image by Adrian N. Bouchard, courtesy of Rauner Special Collections Library.) |

| BASIC Program for solving quadratic equations. Dartmouth hosted a fiftieth anniversary celebration of BASIC on April 30. The celebration included the premiere of a documentary on BASIC, created by filmmakers Bob Drake and Mike Murray. (from the First BASIC Instruction Manual, 1964.)[1] |

References:

- Basic Fifty Web Site.

- the original First BASIC Instruction Manual from 1964 (550 kB PDF File).

- Thomas E. Kurtz, "BASIC Commands," October 26, 2005.

- Harry McCracken, "Fifty Years of BASIC, the Programming Language That Made Computers Personal," Time Magazine April 29, 2014.

- Stephen Cass, "The Golden Age of Basic, IEEE Spectrum, May 1, 2014.