The Human Microbiome

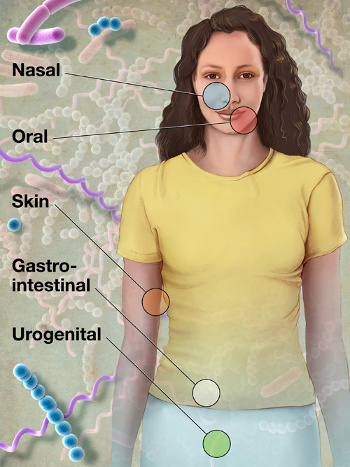

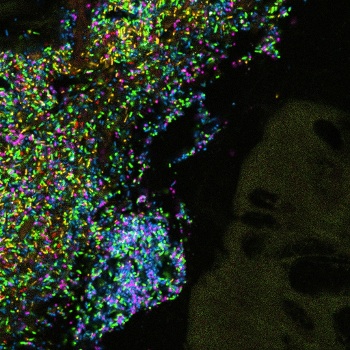

June 18, 2012 The microbiome is the ensemble of microbial communities that live on, and in, the human body. Obviously, something that's living and in such intimate contact with us should have some impact on our health. the National Institutes of Health launched a Human Microbiome Project (HMP) in 2008 to study the microbiomes of 242 healthy humans. genome sequences for the microbiome, and establishing a repository. The project goal is to sequence 3000 genomes to at least a high-quality draft stage. As of this writing, about 25% of this goal has been achieved. The ~200 members of the Human Microbiome Project from nearly 80 research institutions have just published a slew of papers describing their results.[1-9] There were fourteen papers published, two of which were in the June 14 issue of Nature[1-2] and the remaining twelve in Public Library of Science (PLoS) journals.[3-4] These papers describe the analysis of more than 5,000 samples of human and bacterial DNA that resulted in 3.5 terabases of genomic data.[5] Samples were obtained from the the airways, skin, oral cavities, digestive tracts, and vaginas of 242 healthy people ranging from 18 to 40 years old and living around Houston or St. Louis.[4] It's estimated that the number of microbes in our microbiome outnumber our human cells by a factor of ten.[4] The HMP concludes that there are about 10,000 bacterial species in our human microbiome.[5,7] These microbes are thought to contain eight million different protein-coding genes. The human genome contains about 22,000 protein-coding genes, so the microbial protein factories are 360 more diverse.[4] | An Enterococcus faecalis bacterium, normally found in the human gut. (United States Department of Agriculture image). |

"What this means is, there is not just one way to be healthy... There doesn’t have to be one or two 'just right' gut communities, but rather a range of 'just fine' communities."[5]Racially and ethnically related people seemed to have similar microbiomes. However, the differences in microbiome composition didn't matter at a functional level, since the set of microbes in each person performed similar metabolic tasks.[4] The HMP researchers found also that most people carry pathogenic microbes without ill affect. This leads to the problem as to what conditions will lead to disease.[5] Staphylococcus aureus, one strain of which is the difficult to treatMethicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, was found in the noses of about 30 percent of the people.[4] Dirk Gevers, who shared first authorship of one Nature paper,[1] and was an author of the other,[2] compared the Human Microbiome Project to the Human Genome Project.

"Just as the Human Genome Project was 10 years ago, the Human Microbiome Project is intended to be a baseline for future studies of human health and disease... This is a tremendous resource that is now publicly available to the scientific community that allows us to ask how and why microbial communities vary."[4]National Human Genome Research Institute (http://www.genome.gov).

References:

- Curtis Huttenhower, et al. (The Human Microbiome Project Consortium), "Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome," Nature, vol. 486, no. 7402 (June 14, 2012), pp. 207-214; PDF file available, here.

- Barbara A. Methé, et al. (The Human Microbiome Project Consortium), "A framework for human microbiome research," Nature, vol. 486, no. 7402 (June 14, 2012), pp. 215-221; PDF file available, here.

- Susan M. Huse, Yuzhen Ye, Yanjiao Zhou and Anthony A. Fodor, "A Core Human Microbiome as Viewed Through 16S rRNA Sequence Clusters." PLoS ONE, vol. 7, no. 6. Document No. e34242; PDF file available, here.

- Elizabeth Cooney, "Mapping the healthy human microbiome," Broad Institute Press Release, June 13, 2012.

- 'More than One Way to Be Healthy': First Map of the Bacterial Makeup of Humans Relies on MBL Innovations, Insights, Marine Biological Laboratory Press Release, June 13, 2012.

- NIH Human Microbiome Project defines normal bacterial makeup of the body, National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) Press Release, genome.gov June 13, 2012; PDF version available, here.

- Anne Holden, "Consortium of Scientists Map the Human Body's Bacterial Ecosystem," Gladstone Institute Press Release, June 13, 2012.

- Forsyth Scientists Define the Bacteria that Live in the Mouth, Throat and Gut, Forsyth Institute Press Release, June 13, 2012.

- Human Microbiome Project, The NIH Common Fund web site.

- Barbara A. Methé, et al. (The Human Microbiome Project Consortium), "A framework for human microbiome research," Nature, vol. 486, no. 7402 (June 14, 2012), pp. 215-221; PDF file available, here.