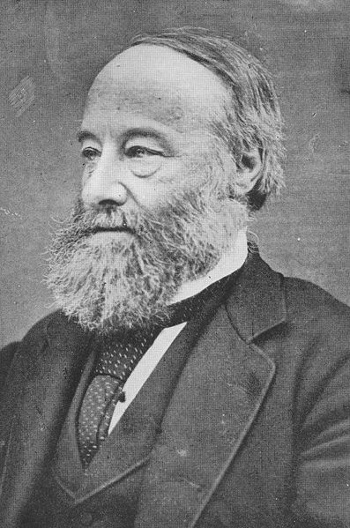

James Prescott Joule

June 14, 2012 My household has a plethora of electrical gadgets that do mechanical work so my wife and I don't need to. In the kitchen, we have a mixer, food processor, dishwasher, and a coffee grinder. We have a pump for our water well, and a circulator pump for our gas-fired boiler. We have a clothes washer and dryer; and, in the garage, we have a garage door opener. I confess that I was too lazy to install the garage door opener, which is still in the box, but, some day... We don't have an electric vehicle, but I see a time when the internal combustion engine will be extinct, at least for passenger vehicles. All these devices have electric motors that convert electrical energy into mechanical energy. Energy may take different forms, but we now realize that it's all the same thing. The unit of energy is the joule. In mechanical terms, a joule is the energy required to apply a force of one newton through a meter's distance; that is, it's a newton-meter (N⋅m). In electrical terms, it's the energy expended when a current of one ampere is passed through a one ohm resistor for one second. The joule is named after James Prescott Joule (1818-1889), an English physicist who is best known for determining the mechanical equivalent of heat. | James Prescott Joule (1818-1889). This photograph is from the book, Britain's Heritage of Science, by Arthur Shuster and Arthur E. Shipley (London, 1917). (Via Wikimedia Commons). |

Q = I2 ⋅ R ⋅ t,in which Q is the heat generated (joules) in the resistor R (ohms) by a current I (amperes) flowing for a time t (seconds). Calorimeters are devices that are used to measure heat. Every calorimeter has its own "personality," so each needs its own calibration. One way to do this is to perform a known chemical reaction and measure its heat. A lot of benzoic acid (C7H6O2) has been burned for this purpose, since this is an easy way to generate heat.

C7H6O2(s) + 7.5 O2(g) -> 7CO2(g) + 3H2O(l) ΔH = 3,227 kJSince my calorimeters were not designed to combust benzoic acid, Joule's law was very important to me for my thermodynamic studies. I would use an electrical current to heat a resistor inside the calorimeter, thereby releasing a known quantity of heat.

| Old data never dies, it just becomes fodder for blog articles. This data trace from a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC) is from an experiment I did about thirty-five years ago. It shows the evolution of heat from the formation of the iron-aluminum intermetallic compound, FeAl3. |

"... The motive power of the electro-magnetic engine is obtained at the expense of the heat due to the chemical reactions of the battery by which it is worked."The mechanical equivalent of heat, relating the quantity of mechanical work to heat, is probably Joule's most important discovery. Benjamin Thompson, a.k.a., Count Rumford, had done some qualitative experiments around 1797 in which he applied the friction of a blunt boring tool to a cannon barrel in water. He found that the water boiled after about two and a half hours.[2] Joule quantified this effect using an apparatus that stirred water in a vessel using the energy obtained in the drop of weights working a pulley system (see photograph). The friction involved in this process heated the water, and the temperature rise gave the measure of the heat evolved.[1]

| James P. Joule's apparatus for the measurement of the mechanical equivalent of heat, now housed in the Science Museum, London. (Photo by Dr. Mirko Junge, via Wikimedia Commons). |

"But, although the mechanism of heat should, in fact, be one of those mysteries of nature which are beyond the reach of human intelligence, this ought by no means to discourage us, or even lessen our ardour, in our attempts to investigate the laws of its operations."[4]

References:

- December 1840: Joule's abstract on converting mechanical power into heat, APS News, vol. 18, no. 11 (December, 2009), p. 2.

- Benjamin Count of Rumford, "An Experimental Enquiry Concerning the Source of the Heat which is Excited by Friction", Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society, vol. 88 (January 1, 1798), pp. 80-102.

- J. P. Joule, "On the Production of Heat by Voltaic Electricity," Proc. R. Soc. Lond., 1837, no. 4, pp. 280-282.

- Benjamin Count of Rumford, "An Experimental Enquiry Concerning the Source of the Heat which is Excited by Friction", Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society, vol. 88 (January 1, 1798), p. 100.

- The scientific papers of James Prescott Joule (1884), archive.org, available in many electronic formats.

- Benjamin Count of Rumford, "An Experimental Enquiry Concerning the Source of the Heat which is Excited by Friction", Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society, vol. 88 (January 1, 1798), pp. 80-102.