Gold, Frankincense and Myrrh

December 23, 2011 - January 1, 2012 holiday season is upon us. One popular holiday pastime is seeing how expensive the gifts in the "Twelve Days of Christmas song" would be if purchased in the current year. Since these are common items, their cost as a percentage of household income is probably not that much changed from the time the song was written, about the time of the American Revolution. According to Wikipedia, the total cost for 2011 is $101,119.84.[2] About eighteen hundred years before the twelve days song was published, the presentation of the first Christmas gifts was made. These were the gifts of the Magi (a.k.a., "Three Wise Men") to the infant Jesus. The traditional gifts of the Magi are gold, frankincense and myrrh. We all know the nature of gold, but what are frankincense and myrrh? Commiphora myrrha tree, is an aromatic resin like frankincense. Important natural items in the ancient world always have a interesting companion story. Myrrha, the mother of the Greek god, Adonis, was transformed into a myrrh tree after having had intercourse with her father. As a result of this union, Myrrha gave birth to Adonis while in tree form. And we think the plots of some television shows are exaggerated! The trees that yield frankincense and myrrh are small, desert trees that yield their sap in far less abundance than sugar maple trees (Acer saccharum), so frankincense and myrrh are expensive items. Gold, at a present value of about $1,613 an ounce, would still consume the majority of your gift card, but frankincense resin is priced at about $58 per kilogram, and myrrh is about twice as expensive.[3] A recent journal article projects a huge decline in the number of boswellia trees, which would lead to a dramatic price increase.[3-6] Since the trees that yield frankincense and myrrh grow in arid areas, climate change could have a profound effect on their survival.[5] Plant husbandry is important also. About 3 kilograms of resin can be taken from each tree, but after tapping a tree for about five years, the tree should be left to rejuvenate for another five years to maximize profit.[5] The temptation is always there to tap a tree annually for near-term profit. A team of scientists from the Forest Ecology and Forest Management Group, Wageningen University (Wageningen, The Netherlands), the Ecology and Biodiversity Group, Utrecht University (Utrecht, The Netherlands) and the Forestry Research Center, Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia) have performed the first large-scale demographic study of boswellia trees. They collected data on twelve populations of these trees in northern Ethiopia, looking at the survival, growth and fecundity of 4370 trees and 2228 seedlings over a 2-year period.[6] Although small seedlings were abundant, none developed into persistent saplings during the study period. There was a 6–7% per year adult mortality caused by beetle attacks and fire. Trees that were tapped for their resin had higher diameter growth rates and fecundity than those that were not, a likely consequence of selection of the best trees by the resin tappers.[6] If the current scale of boswellia resin tapping continues, the study authors project a 90% decline in boswellia tree populations within 50 years. In the near term, this scales to a 50% decline in frankincense production after fifteen years. Modeling showed that frankincense production could be sustained at present levels only if a 50-75% reduction in adult mortality could be achieved.[6] Factors that affect the survival of boswellia trees are fires, cattle grazing, and attack by the long-horn beetle. The beetle lays its eggs under the parchment-like bark of boswellia trees. Once a tree is lost from its environmental niche, other species of trees can take over the ground patch and claim the area.[5] The study found that a population of boswellia trees in a region not subject to cattle grazing and burning had overall better health and lower mortality rate.[4] Study coauthor, Frans Bongers, an ecologist at Wageningen University in the Netherlands, is quoted by the BBC as saying,"The forests that remain are declining because the old individuals are dying continuously, and there there no new individuals coming into the system. That means that the forests are running out of trees." [5]As corporate managers are wont to say, there are no problems, just opportunities. There may come a time when the price of frankincense and myrrh will justify an effort by chemists to synthesize them in the laboratory; or for biologists to identify and splice the particular resin-producing genes into the DNA of other tree species. That would be scientists' holiday gift to the world.

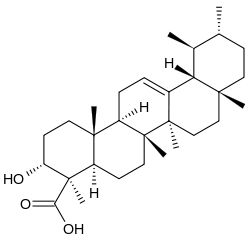

References:

- Thomas Nast, "Merry Old Santa Claus," a drawing from the January 1, 1881 edition of Harper's Weekly, via Wikimedia Commons.

- Christmas Price Index page on Wikipedia.

- Charlie Cooper, "Who'd be a wise man? Gold's gone through the roof, frankincense is 'doomed', and as for myrrh...," Independent (UK), December 21, 2011.

- Frankincense production 'doomed', Guardian (UK), December 21, 2011.

- Mark Kinver and Victoria Gill, "Frankincense tree facing uncertain future," BBC News, December 20, 2011

- Peter Groenendijk, Abeje Eshete, Frank J. Sterck, Pieter A. Zuidema and Frans Bongers, "Limitations to sustainable frankincense production: blocked regeneration, high adult mortality and declining populations," Journal of Applied Ecology, vol. 48, no. 6 (December 20, 2011), doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2011.02078.x.

- Christmas Price Index page on Wikipedia.