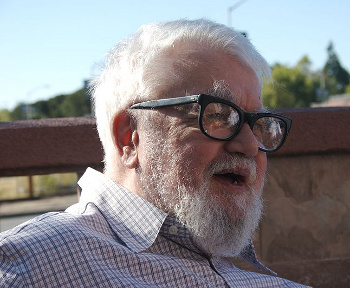

John McCarthy

November 1, 2011 The best knowledge workers are the ones who are adept at organizing their thoughts. A few minutes outlining a computer program on a piece of scrap paper can save needless hours of patchwork later. The epitome of organization in a computer language, itself, is Lisp. Lisp is such a different type of language, that when the US military decided that all its programs would be written in Ada, Lisp was allowed as an exception. John McCarthy, artificial intelligence pioneer and creator of Lisp, died on October 24, 2011, at age 84.[1-8] | John McCarthy (Via Wikimedia Commons). |

"It is as if the geneticists after 1910 had organized fruit fly races and concentrated their efforts on breeding fruit flies that could win these races."[2]There was early optimism for AI. McCarthy predicted that a computer would defeat a human chess master in the 1970s. It took two decades longer.[3] Failed predictions such as this may have been responsible for AI's falling out of favor in the 1980s and 1990s. Sebastian Thrun of Google, as quoted in Wired, says that "there was a mismatch between the promises that were made and reality. People realized we couldn't duplicate human intelligence."[4] McCarthy also worked on the development of early computer time-sharing systems.[1,4-5] He was the first to propose a time-sharing model of computing, looking forward to the day that "computing may some day be organized as a public utility, just as the telephone system is a public utility."[2] His involvement with time-sharing was possibly the reason that he dismissed personal computers as "toys."[1] Personal computers have changed the computing model from public utility to home appliance, although corporate greed is attempting to push it back into a centralized and monetized environment. McCarthy's most ardent desire was the establishment of mathematical rigor in computing. He wrote in a 1995 paper that "He who refuses to do arithmetic is doomed to talk nonsense."[7] Cryptography pioneer, Whitfield Diffie, who also worked at the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, is quoted in the Daily Mail as saying that McCarthy had the idea of electronic commerce in the 1970s and presented it in a conference in France.[5] McCarthy worked also on a robotic arm system, controlled by computer vision, that could stack and arrange objects.[6] McCarthy seemed to share some of Norbert Weiner's personality traits, possibly because they were both prodigies. He was intensely focused, shunning small-talk and sometimes appearing rude, simply because his mind was elsewhere.[6] But such outward appearances were offset by his true nature and self-deprecating sense of humor. Said Ed Feigenbaum, professor emeritus of computer science at Stanford, "He could be blunt, but John was always kind and generous with his time, especially with students, and he was sharp until the end. He was always focused on the future. Always inventing, inventing, inventing. That was John."[6] AI, of course, came with a truck-load of philosophical questions, such as whether thermostats could be said to have beliefs (see figure).[2] McCarthy wrote a paper, "Free Will - Even for Robots, and Deterministic Free Will," in which he examined ideas about robot decision-making. He also wrote a science fiction story, "The Robot and the Baby," to explicate interaction between AI objects and people.[2] McCarthy possessed an electronic copy of Logicomix, a graphic novel about the foundations of mathematics.[2]

| Is it just me, or does it feel cold in here? One question in AI is whether thermostats have belief. Photo by Vincent de Groot, via Wikimedia Commons (Note Celsius scaling). |

"We show that interstellar travel is entirely feasible with only small improvements in present technology provided travel times of several hundred to several thousand years are accepted."[6]

References:

- Obituary - John McCarthy, Telegraph (UK), October 26, 2011.

- Jack Schofield, "John McCarthy obituary - US computer scientist who coined the term artificial intelligence," Guardian (UK), October 25, 2011.

- Iain Thomson, "Father of Lisp and AI John McCarthy has died," The Register (UK), October 24, 2011.

- Cade Metz, "John McCarthy - Father of AI and Lisp — Dies at 84," Wired News, October 24, 2011.

- Lee Moran, "'He was always inventing, inventing, inventing': Father of artificial intelligence dies, aged 84," Daily Mail (UK), October 26, 2011

- Andrew Myers, "Stanford's John McCarthy, seminal figure of artificial intelligence, dies at 84," Stanford Report, October 25, 2011.

- Stephen Miller, "John McCarthy (1927-2011) - Computer Scientist Coined 'Artificial Intelligence'," Wall Street Journal, October 26, 2011.

- Katie M. Palmer, "(Remembering (John (McCarthy (1927 - 2011))))," IEEE Spectrum, October 25, 2011.

- John McCarthy's Stanford University Homepage.

- William Aspray, Interview with John McCarthy, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, March 2, 1989.

- Jack Schofield, "John McCarthy obituary - US computer scientist who coined the term artificial intelligence," Guardian (UK), October 25, 2011.