Robert A. Helliwell

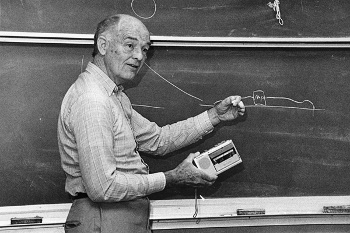

June 16, 2011 Transistors were still expensive when I was a young experimenter, and it was only when I was in seventh grade that I built my first transistorized circuit. This was a one transistor "lie detector" that my science teacher and I tested on an obviously nervous young student. From what I can remember, the circuit measured skin resistance with the idea that you sweat when you're nervous, and this will lower skin resistance. Our data were inconclusive. Shortly after that, I built several transistorized circuits that really interested me. These were VLF (Very Low Frequency) receivers of the audible frequency band of 20-20,000 Hz that monitored the natural radio emissions of the Earth environment. They would also indicate whenever anyone in the neighborhood was using a large electric motor, or if there was a lightning storm on the way. Very low frequency signals, called spherics, short for radio atmospherics, are produced by distant lightning strikes exciting the ionosphere. One interesting class of these are whistlers, so called because they have a signal that descends in frequency. Every morning, I would tune into the dawn chorus that consisted of random chirping sounds not unlike birdsong. The dawn chorus appears to be related to the Earth's magnetosphere. Robert A. Helliwell, a pioneer in radio observations of this sort, died on May 3, 2011, at age ninety.[1-5] | Robert A. Helliwell. (Stanford University Image). |

References:

- Melissae Fellet, "Robert Helliwell, Radioscience and Magnetosphere Expert, Dead at 90," Stanford Report, May 20, 2011.

- Melissae Fellet, "Robert Helliwell, Radioscience and Magnetosphere Expert, Dead at 90," Scientific Computing, May 20, 2011.

- Thomas H. Maugh II, "Robert Helliwell, Electrical Engineer who Expanded Understanding of Earth'S Atmosphere, Dies at 90," Los Angeles Times, June 13, 2011.

- Electrical Engineering Prof. Helliwell Dies at 90, Stanford Daily News, May 24, 2011.

- Listening in on lightning, Stanford Engineering Web Site.

- NASA VLF Sounds Page

- Robert A. Helliwell, Professor Emeritus of Electrical Engineering, Stanford Personal Web Site.

- A. C. Fraser-Smith, A. Bernardil, P. R. Mccwiil, M. E. Ladd, R. A. Helliwell, and 0. G. Villard, Jr., "Low Frequency Magnetic Field Measurements Near the Epicenter of the M 7.1 Loma Prieta Earthquake," Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 17, no. 9 (August, 1990), pp. 1465-1468.

- R. Raghuram, T. F. Bell, R. A. Helliwell, and J. P. Katsufrakis , "A Quiet Band Produced by VLF Transmitter Signals in the Magnetosphere," Geophys. Res. Lett., vol. 4, no. 5 (May, 1977), pp. 199-202.

- J. Luette, C. Park, and R. Helliwell, The Control of the Magnetosphere by Power Line Radiation, J. Geophys. Res., vol. 84, no. A6 (June, 1979), pp. 2657-2660.

- J. Witzel, "Sferic Detection-The First Line of Defense," IEEE Instrumentation & Measurement Magazine, vol. 4, no. 1 (March, 2001), pp. 52-53.

- The Stanford University VLF Group.

- Melissae Fellet, "Robert Helliwell, Radioscience and Magnetosphere Expert, Dead at 90," Scientific Computing, May 20, 2011.