Gale Crater

August 31, 2011 Words, especially proper names, tend to mean different things to different people. The name, "Gale," has been in the news a lot, since NASA has chosen Gale Crater on Mars as the destination for its Curiosity Rover (a.k.a., Mars Science Laboratory).[1-7] I had never heard of Gale Crater, so when I read, "Gale," I had two other associations for the word. Those were for two actors named, "Gale," who are related to each other in a several-degrees-of-separation way. Gale Gordon (1906-1995) was a popular character actor. One of his first roles was as Principal Osgood Conklin on the "Our Miss Brooks" radio program, subsequently adapted for television. He played this same type of stuff-shirted, blustery character his entire career, most notably in the Lucille Ball television sitcoms.[8] Gale Storm's (1922-2009) first television series was "My Little Margie" (1952). This television series was just intended to be a summer replacement for "I Love Lucy," (that's the several-degrees-of-separation linkage), but it was very popular in reruns.[9] Gale Storm returned in 1956 with another series, "The Gale Storm Show," in which she played a cruise ship director. After a long hiatus, she appeared on "The Love Boat" in 1979.[9] I confess that I enjoyed watching "The Love Boat," which was a way-point for actors on their way to retirement. Giovanni Schiaparelli's 1886 map of Mars. Elysium Planitia, home to Gale Crater, sits in the lower left-hand quadrant. (Via Wikimedia Commons).

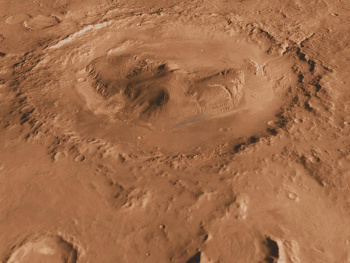

Gale crater has a unique geological structure. The 96 mile (154 kilometer) diameter crater has a central, layered mound, three miles (5 kilometer) high, at its center. The landing area for the rover contains a very dense and very brightly colored type of rock that's unique to the crater. The crater may have contained an ancient lake, since orbital spectroscopy has detected clay minerals and sulfate salts. There's an alluvial fan near the landing zone that most likely consists of sediment carried along by water.[1]

Giovanni Schiaparelli's 1886 map of Mars. Elysium Planitia, home to Gale Crater, sits in the lower left-hand quadrant. (Via Wikimedia Commons).

Gale crater has a unique geological structure. The 96 mile (154 kilometer) diameter crater has a central, layered mound, three miles (5 kilometer) high, at its center. The landing area for the rover contains a very dense and very brightly colored type of rock that's unique to the crater. The crater may have contained an ancient lake, since orbital spectroscopy has detected clay minerals and sulfate salts. There's an alluvial fan near the landing zone that most likely consists of sediment carried along by water.[1]

| An oblique, southwards-looking view of Gale crater. The Curiosity Rover landing site is north of the mound inside the crater. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU/UA Image). |

• Mastcam - Mast Camera.

• ChemCam - Chemistry and Camera.

• RAD - Radiation Assessment Detector.

• CheMin - Chemistry and Mineralogy.

• SAM - Sample Analysis at Mars.

• DAN - Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons.

• MARDI - Mars Descent Imager.

• MAHLI - Mars Hand Lens Imager.

• APXS - Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer.

• REMS - Rover Environmental Monitoring Station.

Mars Science Laboratory (Curiosity Rover). (NASA/JPL-Caltech Image).

The Curiosity rover contains so much instrumentation that simple solar power would not have been enough. The rover uses a radioisotope thermoelectric generator, as I described in a previous article (Radioactive Heat, July 26, 2011), for its electrical power and heat.

The rover's size, typically described as being as large as a sport utility vehicle, and 900 kg weight, required a different sort of landing mechanism than the "bouncing ball" approach of the Spirit and Opportunity Rovers.[3] The landing will be accomplished by a rocket-powered sky crane that will suspend the rover on tethers in its descent to the Martian surface.[4]

It was impossible to reach a consensus from scientists as to where to land this Martian probe. The decision process started in 2006 when more than 100 scientists in several worldwide workshops considered about 30 potential landing sites.[4] In 2008, a shortened list had crater sites in the top three positions, but astrobiologists favored sites lower on the list with ancient lakebeds and deltas. These seemed to them more likely to hold organic residues of life than the deep crustal topography of the craters.[7]

The final decision, from a short list of four candidates, was made by mission principals in a "smoke-filled room."[7] The decision was not popular in some circles. Some scientists are concerned that Gale Crater is, in fact, too unique. It's a geologic mystery.[7]

Carlton Allen, curator of astromaterials at NASA's Johnson Space Center (Houston, Texas), thinks Gale's unique features should be a cause for concern, not curiosity. Allen is quoted in Science as saying, "This is a one-shot, billion-dollar mission, and you're talking about going to a place [that] we have severe questions about how it formed."[7]

The Curiosity Rover mission was originally scheduled for launch two years ago, but there were technical problems which caused a long delay until the next match of the orbits of Earth and Mars. The original mission cost of $1.6 billion now stands at $2.5 billion.[6] NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology (Pasadena, California), manages the Mars Science Laboratory Project.[4]

Mars Science Laboratory (Curiosity Rover). (NASA/JPL-Caltech Image).

The Curiosity rover contains so much instrumentation that simple solar power would not have been enough. The rover uses a radioisotope thermoelectric generator, as I described in a previous article (Radioactive Heat, July 26, 2011), for its electrical power and heat.

The rover's size, typically described as being as large as a sport utility vehicle, and 900 kg weight, required a different sort of landing mechanism than the "bouncing ball" approach of the Spirit and Opportunity Rovers.[3] The landing will be accomplished by a rocket-powered sky crane that will suspend the rover on tethers in its descent to the Martian surface.[4]

It was impossible to reach a consensus from scientists as to where to land this Martian probe. The decision process started in 2006 when more than 100 scientists in several worldwide workshops considered about 30 potential landing sites.[4] In 2008, a shortened list had crater sites in the top three positions, but astrobiologists favored sites lower on the list with ancient lakebeds and deltas. These seemed to them more likely to hold organic residues of life than the deep crustal topography of the craters.[7]

The final decision, from a short list of four candidates, was made by mission principals in a "smoke-filled room."[7] The decision was not popular in some circles. Some scientists are concerned that Gale Crater is, in fact, too unique. It's a geologic mystery.[7]

Carlton Allen, curator of astromaterials at NASA's Johnson Space Center (Houston, Texas), thinks Gale's unique features should be a cause for concern, not curiosity. Allen is quoted in Science as saying, "This is a one-shot, billion-dollar mission, and you're talking about going to a place [that] we have severe questions about how it formed."[7]

The Curiosity Rover mission was originally scheduled for launch two years ago, but there were technical problems which caused a long delay until the next match of the orbits of Earth and Mars. The original mission cost of $1.6 billion now stands at $2.5 billion.[6] NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology (Pasadena, California), manages the Mars Science Laboratory Project.[4]

References:

- Mars Science Laboratory Home Page.

- Mars Science Laboratory Page at JPL

- Suzanne Presto, "Curiosity Rover Bound for Mars' Gale Crater," Voice of America, July 22, 2011.

- Guy Webster and Dwayne C. Brown, "NASA's next Mars rover will land at the foot of a layered mountain inside the planet's Gale crater," NASA Press Release No. 2011-222, July 22, 2011.

- Lester Haines, "Nuclear Mars tank to roam imposing crater," The Register (UK), July 22, 2011.

- Kenneth Chang, "NASA Picks Rover Destination: Mountain on Mars," The New York Times, July 22, 2011.

- Richard A. Kerr, "How an Alluring Geologic Enigma Won the Mars Rover Sweepstakes," Science, Vol. 333 no. 6042 (July 29, 2011), pp. 508-509.

- Gale Gordon Page on the Internet Movie Database

- Gale Storm Page on the Internet Movie Database.

- Mars Science Laboratory Page at JPL